Paris Terror Attacks Renew Encryption DebateParis Terror Attacks Renew Encryption Debate

The terror attacks in Paris on Nov. 13 have reignited a long-running debate about whether device makers and app developers should be required to give government agencies a "back door" or hand over encryption keys that would enable them to access data created and shared by individuals and groups.

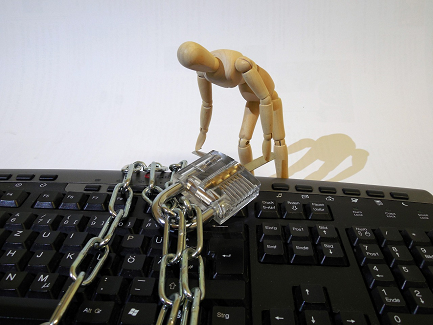

Insider Threats: 10 Ways To Protect Your Data

Insider Threats: 10 Ways To Protect Your Data (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

As the investigation continues into the terror attacks that rocked Paris on November 13, the topic of strong encryption on devices and apps is gaining renewed attention.

Some media reports have alleged that the attackers were able to communicate under the radar of international intelligence agencies in part because they may have used readily available apps that offer strong encryption. This has reignited a long-running debate about whether devicemakers and app developers should be required to give government agencies a backdoor or hand over encryption keys that would enable them to access an individual's or group's data.

Government agencies, including the FBI in the US, have long expressed concern about strong encryption on mobile devices and apps. In July, FBI Director James Comey appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee to argue for legal support to weaken strong encryption, which he claimed obstructs criminal investigations. Still, the Obama Administration decided last month not to seek legislation that would force backdoors into encryption methods.

According to an article in The New York Times, European officials made a direct link between the bombers and the use of encryption. The article states: "The attackers are believed to have communicated using encryption technology, according to European officials who had been briefed on the investigation but were not authorized to speak publicly. It was not clear whether the encryption was part of widely used communications tools, like WhatsApp, which the authorities have a hard time monitoring, or something more elaborate. Intelligence officials have been pressing for more leeway to counter the growing use of encryption."

An article in Wired outlines four reasons why encryption backdoors aren't a panacea, particularly when it comes to gathering intelligence about potential acts of terror.

In May, dozens of prominent technologists, civic organizations, and companies signed an open letter to President Obama urging him to preserve strong encryption in order to protect national security and US business interests. "Whether you call them 'front doors' or 'back doors,' introducing intentional vulnerabilities into secure products for the government's use will make those products less secure against other attackers," the letter argued, adding that any such requirement would harm the market for such products abroad.

[When good data intentions go bad. Read 14 Creepy Ways To Use Big Data.]

This summer, a group of cryptography experts published a similar letter warning that demands for exceptional access to encrypted data by law enforcement are fraught with problems. "We find that [granting law enforcement exceptional access] would pose far more grave security risks, imperil innovation, and raise thorny issues for human rights and international relations," the letter said.

It remains to be seen whether the Paris attacks will change the political will in the US and other nations when it comes to encryption backdoors.

The Washington Post obtained an August email from Robert Lott, lawyer to the intelligence community, that said, "The legislative environment is very hostile [toward encryption backdoors] today. It could turn in the event of a terrorist attack or criminal event where strong encryption can be shown to have hindered law enforcement."

Et voilà, Paris.

Is strong encryption and talk of backdoors for law enforcement a red herring? Adversaries can and will find ways to communicate using, for example, common non-encrypted devices, such as a PlayStation 4 videogame console, or rely on trusted human couriers. They will use encryption tools available in places without encryption bans, or develop their own encryption.

Meanwhile, reports are surfacing that French and Belgian intelligence services were aware of the likely suspects in the Paris attacks before the attacks took place.

As we consider the injuries and loss of human life caused by acts of terror in Paris and around the world, we hope that a nuanced debate is possible. Encryption is but one small piece in a very large, and daunting, intelligence puzzle that spans the worlds of technology, telecommunications, and all manner of organizations in the public and private sector.

Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Should governments be allowed backdoors into encryption services? Is strong encryption to blame for helping terrorists evade law enforcement? Have the Paris attacks changed the way you view these issues?

**New deadline of Dec. 18, 2015** Be a part of the prestigious information Elite 100! Time is running out to submit your company's application by Dec. 18, 2015. Go to our 2016 registration page: information's Elite 100 list for 2016.

About the Author

You May Also Like