Could the DOJ’s Antitrust Trial vs Google Drive More Innovation?Could the DOJ’s Antitrust Trial vs Google Drive More Innovation?

Google’s ad tech will also face antitrust claims in court -- will this signal limits on big tech that allow for more competition?

At a Glance

- Echoes of US Versus Microsoft Antitrust Case

- Is Big Tech Too Big to Challenge?

- DOJ Takes Action as Policymakers Debate

The trial began recently for the Department of Justice’s antitrust lawsuit versus Google targeting the company’s dominance in search with yet another antitrust trial, for a suit announced back in January regarding digital ad technologies, still in the offing. As different branches of government pursue more active roles in regulating how big tech companies conduct business -- and the sway such companies hold over the public and the market -- stakeholders in the tech scene are closely watching the trials unfold.

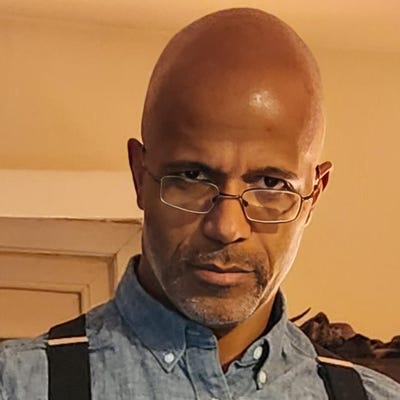

Tech policy advisor Tom Kemp, and author of “Containing Big Tech: How to Protect Our Civil Rights, Economy, and Democracy,” says the current antitrust trial, as well as the one on the horizon for Google’s ad tech business, may indicate more regulatory action to come. “There’s rumblings that the FTC [Federal Trade Commission] may go after Amazon for preferencing its own products,” he says, “and attacking the fact that Amazon does basics and they’re able to gather all this intel about what products they’re selling. It’s definitely going to be ‘Antitrust Season’ for the next few years.”

Kemp says the current scrutiny on Google is comparable to the United States v. Microsoft antitrust suit in 2001, which called into question Microsoft’s influence over PC manufacturers and the overt, preinstalled presence of the Internet Explorer web browser.

“Basically, Microsoft told all the OEMs that you could only bundle Internet Explorer; and Netscape’s market share went from 90% to very small,” he says. “Internet Explorer was able to become the dominant browser because basically, Microsoft was able to buy or contractually get all the shelf space. The DOJ sought the breakup of Microsoft’s businesses, but the case ended in a settlement that allowed other web browsers to be bundled with computers," Kemp says. “The ironic thing is that completely opened up the internet market and really made way for Google and others to happen.”

The thought process among regulators, he says, might be that the antitrust case against Microsoft brought about change and created opportunities for more competition -- a similar attempt with Google may be worth the effort. “This particular antitrust case really focuses narrowly on the company’s popular search engine, and it alleges that Google uses their 90% market share to illegally throttle competition in search and search advertising,” Kemp says.

CTO Jimmie Lee with XFactor.io, a developer of a business decision platform, says he can understand some of Big Tech’s perspective, having come from Facebook parent Meta and Microsoft. “When you’re in the company, it feels very different from being on the outside,” he says. “From the inside, you see the strength of the technology and how you can better add security and privacy and features and functionalities throughout the entire stack and workflow.”

Thus, the features, from the tech company’s perspective, can seem to make life much easier for the end user. However, from the outside looking in, it can look like Big Tech wields unchecked power. “There are decisions that they make, because they’re so powerful, that nobody in the world can challenge them on,” Lee says. “There’s no other equalizer. There’s no other balancing act.”

As far as the rest of the tech scene goes, he says startups have no early worries about antitrust issues, as it could take decades to approach that level of market dominance that would warrant regulatory scrutiny. Splitting up Big Tech into more manageable, regulated organizations could create another quandary that Lee points out: Who could provide the same services at the scale the market now demands if they are forced to break up?

Splitting up Big Tech into more manageable, regulated organizations could create another quandary that Lee points out: Who could provide the same services at the scale the market now demands if they are forced to break up?

“What’s going on with this antitrust issue is actually is a symptom of a much larger problem, and that is how we as a country, specifically the US, treats patents and celebrates technology,” Lee says, “to the point where companies and organizations and individuals feel like they must hoard it and must not share with others.”

One of the things Silicon Valley tended to get right, he says, was the handling of contracts where a larger company bought access to tech from startups with terms that allowed the smaller companies to retain their full IP rights so they could sell the technology to others. “That needs to happen a lot more, not only just from the larger companies, but it should be motivated, it should be encouraged from the US government level,” Lee says. That way individuals and organizations would be celebrated for their innovations and the genius behind them, rather than focusing on protectionist strategies for patents and tech.

Loosening up Big Tech’s chokehold on various sectors via antitrust suits might clear the way for more innovation. The government argues, Kemp says, that Google has maintained a monopoly not by making a better product but rather by making it harder for consumers to find different search engine options. “What the government is saying is that Google is locking out rivals because it’s going out and doing these deals to make Google the default,” Kemp says. “The most significant one is that they pay Apple at least $15 billion and another example is that on Android, according to DuckDuckGo, it takes 15 steps for someone to switch to DuckDuckGo as the search engine on Android.”

The payment to Apple is in reference to maintaining Google as the default search engine on Apple’s Safari web browser.

The ramifications of such an antitrust lawsuit could change the dynamics of how big tech functions in this country, especially at a time when data privacy, data ownership, and the proliferation of generative AI are of increasing concern. With slow action on the legislative front to establish guardrails on such matters, it may be up to regulators to enforce existing laws to corral this sector.

“It’s really up to the Department of Justice, the antitrust, to go after these companies if something’s going to be done,” Kemp says. The concern of the DOJ has, he says, is that Google and other big tech companies are very dominant in large digital markets that are increasingly becoming important, precipitating the desire to break them up. Google’s search engine is free use, and some historic looks at antitrust asked what the big deal is if there is no cost to consumers. However, Kemp says there is a newer perspective taking shape. “Lina Khan at the FTC and Jonathan Kanter at the DOJ are saying, ‘No, you really need to look at the impact on competition.’” (Khan is FTC Chair and Kanter is DOJ's assistant attorney general for antitrust.)

The fear, he says, is that big tech incumbents could stifle new ideas from entrepreneurs and chase away venture capital. That could lead to big tech being too big to care, Kemp says, and not focus on the concerns of the public, such as data collection and privacy. “If Google has dominant 90% market share, they’re going to collect as much information,” he says, “but if they had more competition then that would be better.”

Read more about:

AntitrustAbout the Author

You May Also Like