Cloud Standards: Bottom Up, Not Top DownCloud Standards: Bottom Up, Not Top Down

IT has good reason to demand standardization in SaaS, IaaS and PaaS offerings. But what's interesting is that vendors themselves are just as interested, and in many cases, are driving standards efforts.

There's a growing demand for standards to bring some sanity to the cloud computing market. Both buyers and sellers have their reasons to want common ways to do things such as transfer data from one cloud-based app or infrastructure to another. But the competition to be in control is fierce. "The Internet had the IETF, which wrangled people and protocols," says Mathew Lodge, VP of cloud services at VMware. "But in the cloud, the standardization landscape is so fragmented. There isn't a central body or forum or place, although lots of people and organizations are trying to be that."

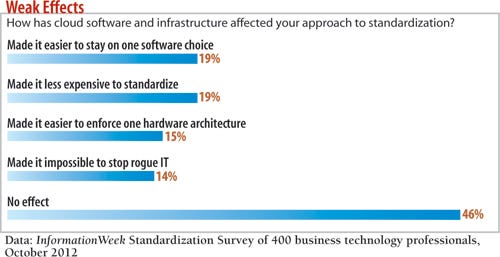

Two main factors drive demand for standards. Cloud vendors want to show they can meet companies' security requirements, since that's the biggest roadblock to adoption. IT pros also see value in formalized standards for cloud services, according to the 400 respondents to our information Standardization Survey: 89% rate standards for cloud infrastructure vendors such as Amazon, Microsoft Azure or Rackspace as extremely (53%) or somewhat (36%) helpful to their organizations; 85% say the same about software-as-a-service. Why? Would-be cloud customers want to avoid getting locked in to one vendor, so investments in cloud services now don't end up limiting future flexibility.

CIOs are right to be wary. When a cloud vendor raises its rates or lets its service quality decline -- or worse, shuts its doors -- IT may be left scrambling. These aren't just theoretical concerns. Amazon Web Services, the dominant provider of infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS), had three major outages in 2012, and Gmail, the most widely used cloud email provider, had two major outages last year. In late 2011, Google raised prices for its platform-as-a-service (PaaS) offering, App Engine, by more than 100% for many customers. On the flip side, keeping open the option to switch spurs competition and lets companies jump on better deals; Amazon, for example, cut storage-as-a-service prices 20% last year, prompting Google to match. And it's not just private enterprises worried about being tied down. The U.S. Department of Defense recently hired cloud computing strategy firm Fusion PPT to identify cloud standards and best practices to avoid lock-in.

Our full report on cloud standards is free with registration.

Our full report on cloud standards is free with registration.

What you'll find:

Guide to what makes a good standard, cloud or otherwise

A sneak peek at the results of our new Standardization Survey

Prognostications from a dozen cloud experts

Though demand for cloud service standards is growing, the conventional top-down model no longer holds. Standards today are more likely to spring organically from wide adoption of the approaches of one vendor or a small cadre, and we expect to see more de facto than formal standards in the cloud era. Simply promulgating a standard -- even if done by a widely respected standards-developing nonprofit -- isn't enough to make it stick. The pace of innovation with cloud services is just too rapid. Vendors are updating their offerings on a monthly basis, whereas standards organizations usually take years to finalize new specs.

So why do we need cloud standards? For starters, to compare services. Even for something as straightforward as CPUs, cloud providers have created their own measurement units: Amazon Web Services has the Elastic Compute Unit, Google has the Google Compute Engine Unit and Microsoft Azure provides the clock speed of its processors.

One relatively bright spot is security, thanks to the Cloud Security Alliance. CSA member organizations, including most large cloud providers, work together to define best practices in security, and the CSA offers a number of useful resources, many of which are becoming de facto standards. For example, the CSA Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM) is a framework for implementing good cloud data center security practices. It provides detailed security concepts and principles in 13 domains and coordinates with security standards such as ISO 27001, COBIT, PCI, HIPAA and FedRAMP. The CSA's Security, Trust and Assurance Registry is another useful resource. It contains responses from cloud service providers to questions raised by the CCM. The registry has responses from major IaaS vendors including Amazon, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft, SoftLayer and Verizon Terremark, as well as SaaS vendors, such as Box.com and Microsoft Office 365. One caveat: The CSA doesn't independently verify answers.

Sadly, the work done by the CSA hasn't been replicated outside the security realm. So here's a look at the state of standards in the three key areas IT needs to evaluate: portability, interoperability, and provisioning and orchestration.

Portability

Standards for cloud portability ideally will enable IT to port applications and data from one provider to another. There are three potential components of portability: data (for all cloud services), configuration (for most cloud services) and images (for IaaS services). Let's look at these by service type.

>> SaaS: Portability with SaaS is fairly straightforward: Either you can export data and configuration from a provider or you can't. Unfortunately, whether export capabilities actually prevent vendor lock-in isn't quite as clear. Can you export the data in a timely and reasonable fashion? Can your alternative vendor import the exported data? While the DataPortability Project promotes standards and policies around data transfers, it's in early stages. Expect to do application-specific investigative legwork.

>> IaaS: An IaaS deployment consists of data, virtual machine images and server configuration, including software installed on the image after launch. IaaS vendors, by definition, export data, so the only question is, how difficult will the process be? Exporting 500 GB from a database running on an IaaS virtual machine to another major vendor is fairly simple, but it may take the better part of a day. On the other hand, when exporting 500 GB of records from a cloud database-as-a-service (like DynamoDB), the transform and load process into another vendor's service (assuming such a service exists) is hit or miss, and it also may take much longer. There aren't any significant standards in data portability for IaaS vendors at this point.

There is, however, a fairly clear standard for image portability: Open Virtualization Format, released by the Distributed Management Task Force and created by Dell, HP, IBM, Microsoft, VMware and XenSource. Still, "really large image sizes break down the standard," warns Michael Biddick, CEO of Fusion PPT and an information contributor. "And if you're moving among different hypervisors, you have to make some changes to the OVF files to make the images work." That said, OVF is about as mature a cloud standard as you'll find and, generally speaking, does deliver on image portability.

>> PaaS: While using PaaS can expose you to some lock-in risk because these vendors tend to rely on one IaaS provider, migrating shouldn't be difficult. In an ideal PaaS deployment, you bring your own code and data and rely on the PaaS vendor for the server configuration that you would have had to do yourself with IaaS, so switching PaaS services should be simple. How well that theory matches reality depends on your vendor. Heroku, for example, presents a fairly straightforward export path, whereas Google App Engine's data extraction process is painful in comparison. The good news is that a number of leading technology vendors, including Oracle, Rackspace and Red Hat have, through the standards body Oasis, proposed the Cloud Application Management for Platforms spec, which is designed to make porting applications among PaaS vendors much easier.

Interoperability

Here we're talking the ability to share cloud services across multiple environments, including a company's own data center, using a private cloud architecture or colocated, noncloud services. Some of the strongest cloud standards have sprung up around identity and access management (IAM) in particular, enabling single sign-on and eliminating the need to control access from multiple management interfaces. IAM dramatically simplifies rolling out new services. There are three main standards in cloud IAM:

>> Security Assertion Markup Language, from Oasis, allows cloud applications to leverage the authentication approaches a company is already is using.

>> System for Cross-domain Identity Management, created by Google, WebEx and Salesforce.com but now under the IETF's auspices, lets cloud applications use directory information from within the enterprise to provide information on user and group permissions within cloud applications.

>> OAuth, originally by Twitter and Google but also now under the IETF, allows cloud users to extend access to resources that they control to other cloud services. For example, you can use OAuth to give LinkedIn access to your Twitter account so that LinkedIn can tweet for you.

Provisioning And Orchestration

Of our three areas, provisioning and orchestration is experiencing the most change. The dominant "standard" in cloud provisioning and orchestration today is the Amazon Web Services API. You can find the AWS API in Amazon's own offerings, of course, but also those from CloudStack, Eucalyptus and even OpenStack (as a module). However, Amazon hasn't made the AWS API officially open for use as a standard, and of the above products, only Eucalyptus has a license to use it.

Raj Dutt, senior VP of technology at IaaS provider Internap, believes that restrictive stance limits its potential. "Because other players in the ecosystem have no input into how the AWS API evolves, Amazon is going to find that their API will be less and less relevant," says Dutt.

In fact, for now, the AWS API may be one of the biggest traps lurking in cloud computing. At any point, Amazon could overturn the game board.

Another pseudo-standard in the provisioning and orchestration space is OpenStack, created by Rackspace and NASA and now from the OpenStack Foundation. OpenStack gives organizations, including cloud service providers, the ability to build public and private clouds on commodity hardware. OpenStack is generally viewed as a worthy competitor to VMware, CloudStack and Eucalyptus in the cloud-building space, although the OpenStack Foundation aspires to greater heights. OpenStack's website describes it as the result of "a global software community of developers collaborating on a standard and massively scalable open source cloud operating system." Whether OpenStack is or will be a true standard is a controversial topic among cloud professionals. Dutt says the future is bright for OpenStack now that the foundation has made key governance changes, while Biddick is skeptical. "The process to contribute to OpenStack is pretty informal," he says. "As opposed to the rigor of the IEEE, it's more of an ad hoc jumble of pieces and parts, not driven by a unifying vision."

The safest way to view OpenStack is as an open source project driven by self-interested companies, not as a standard, and proceed accordingly.

Finally, keep an eye on some standards that, while not widely used today, show promise. The Open Cloud Computing Interface offers an open API for managing cloud services, and the somewhat-similar Cloud Data Management Interface, from the Storage Networking Industry Association, offers an open API for managing cloud data. OASIS' Topology and Orchestration Specification for Cloud Applications, is aimed at the larger issue of interoperability and portability by standardizing the life cycle of cloud services. Tosca 1.0 has not yet been released, so it remains to be seen which vendors will adopt it.

About the Author

You May Also Like