Microsoft's Project Natick: Underwater Data Center Takes The PlungeMicrosoft's Project Natick: Underwater Data Center Takes The Plunge

Microsoft aims to explore the possibility of an undersea data center for lower costs and environmental sustainability with its Project Natick.

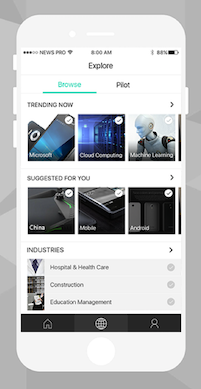

10 Cool Microsoft Garage Projects You Didn't Know About

10 Cool Microsoft Garage Projects You Didn't Know About (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Microsoft is testing an undersea data center through its new research initiative, Project Natick. The watery locale supposedly will lower costs, boost environmental sustainability, and accelerate deployment.

Data centers drain energy and generate massive amounts of heat. This has forced companies to get creative with how they house their data and regulate the temperature of devices storing it.

Deltalis RadixCloud data center, for example, is naturally cooled by chilly air and water in the Swiss Alps, where it occupies a former Swiss Air Force control center. Iron Mountain stores data in an underground limestone mine located in Pennsylvania.

[Is Microsoft's Windows Phone dead? Join the discussion.]

Microsoft is pushing the boundaries of data storage with Project Natick. While the idea of storing a data center underwater at first seems unrealistic, research indicates it could be environmentally friendly and lower costs.

It was Feb. 2013 when Microsoft employee Sean James, who had served on a Navy submarine, introduced the idea of an underwater data center powered by ocean energy. Norm Whitaker, managing director of special projects for Microsoft Research, built a team to work on the project, which kicked off in Aug. 2014.

One year later, a prototype submarine was deployed one kilometer off the California coast. The team was concerned about hardware problems and packed the steel capsule with 100 sensors to gauge motion, pressure, and humidity, reported the New York Times.

The prototype was tested and monitored for 105 days between Aug. 2015 and Nov. 2015. After a successful first try, engineers decided to continue the experiment. The team is currently working on an undersea system three times the size of its prototype, which measured eight feet in diameter.

On Project Natick's website, Microsoft explains how the project could reduce latency for people living near the coast. Half of the world's population lives within 200km of the ocean, it says, and offshore data centers could boost Web speeds because of their close proximity to shore.

Microsoft also said it believes it can mass-produce the underwater capsules and cut the deployment timeframe to 90 days. It currently takes two years to launch a data center on land.

Project Natick is a big idea; one that will require Microsoft to reconsider the traditional maintenance of a data center.

Unlike servers on land, undersea capsules and servers would have to be built for years without maintenance. Microsoft anticipates the lifespan of a capsule will be about 20 years; after that, it will be surfaced and recycled.

Engineers are working to build computers to last five years inside the underwater capsule. After each five-year cycle, the data center would be surfaced, updated with new devices, and redeployed.

An initiative like this will undoubtedly spark environmental concerns. Microsoft notes Natick data centers are cooled by the ocean's temperature, do not consume water, and run on energy produced by the water's movement.

Because it didn't add new energy to the water, the prototype did not significantly alter the surrounding temperature of its undersea environment. Researchers claim they measured an "extremely small amount" of local heat a few inches around the vessel, according to the Times report.

Microsoft's project closely follows news of Facebook's newest data center in Clonee, Ireland. The facility will run on energy generated by renewable power from Ireland's windy environment, but will use an indirect cooling process due to the ocean wind's high salt content.

Are you an IT Hero? Do you know someone who is? Submit your entry now for information's IT Hero Award. Full details and a submission form can be found here.

About the Author

You May Also Like