A Super-Wrong Way To Understand Net NeutralityA Super-Wrong Way To Understand Net Neutrality

Comparisons to electricity and cable TV are off base. Time for an honest discussion.

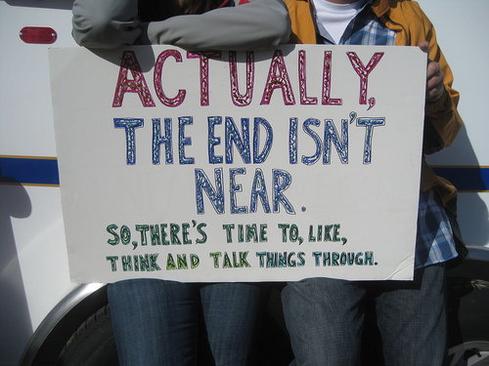

8 Doomsday Predictions From Yesterday And Today

8 Doomsday Predictions From Yesterday And Today (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

I know net neutrality is a complicated issue, but is it too much to expect journalists to get it at least mostly right when they write about it? Apparently so. Case in point is Neil Irwin's New York Times article A Super-Simple Way To Understand The Net Neutrality Debate. Simple, and simply wrong.

Irwin starts out by saying the right way to think about this debate is whether Internet access is more like electricity or cable TV. How about neither? There's no sound comparison to electricity -- for the most part all electrons are the same, but not all bits are the same. Some bits, like email bits, can handle high levels of latency, while others, like video telephony bits, can't. It's why the typical Web video call is jerky.

Irwin even sells electricity short. In fact, not all electrons are equal. Plenty of companies pay extra to their local electric utility to get higher-quality electron flows -- electricity without voltage sags, low electromagnetic interference, capacity switching, etc. As the California Public Utility Commission writes: "The electric utility environment has never been one of constant voltage and frequency. Until recently, most electrical equipment could operate satisfactorily during expected deviations from the nominal voltage and frequency supplied by the utility."

The commission goes on to write that the modern factory has many more complicated electronic devices, and these devices "increase the potential for problems with electrical compatibility because they are not as forgiving of their electrical environment as earlier technologies." Thankfully, we don't have "electron neutrality" advocates pushing for rules to prohibit utilities from varying the quality of electricity they provide to customers based solely on a willingness to pay.

But Irwin really goes off base when he says that without strong Title II net neutrality regulations, the Internet will turn into cable TV, with ISPs deciding what consumers can download based on whether content providers have paid the ISPs. As Irwin puts it: "In a world without net neutrality rules, ISPs [would] be free to throttle the speed with which you could access services that don't pay up, or block sites entirely."

[For another point of view, see Net Neutrality: Let There Be Laws.]

I knew that net neutrality zealots like Free Press's Craig Aaron were disingenuous when they published images like the one in his Huffington Post commentary, showing that without net neutrality rules, ISPs will sell the "Hollywood package" -- for an extra $10 a month you, too, get to stream Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube! Aaron knew this representation is false; he just couldn't resist the propaganda value of the big lie. But I never expected technology journalists to fall for it. Clearly my expectations were too high. Even President Obama must be reading the same pieces, for he too asserts that "we cannot allow ISPs to restrict the best access or pick winners and losers in the online marketplace."

Let's be clear: All major US ISPs have publicly committed to maintaining "best efforts" Internet service, whereby consumers are free to download content from any legal website. The ISPs are no more likely to make best efforts service contingent on payment from content providers than they are to require customers to pay more if they don't watch at least four hours of programming a day.

The concept of best efforts Internet gets to the heart of the matter. Regardless of the size of the pipe, the Internet will experience congestion problems, and congestion is more of a problem for some applications than others. No one rightly cares if his email is delivered 100 milliseconds late. But if Skype traffic is delivered 100 milliseconds late, the connection is virtually unusable. As Chuck Jackson, a former technology staffer for the Federal Communications Commission, states: "in a world of network neutrality, it is likely that aggressive but delay-tolerant applications will thrive and latency-sensitive applications will stumble along."

On wireless networks the problem is even more severe. Does any cellphone user really not want her voice bits prioritized ahead of the movie downloads her neighbor's kid is watching on his iPad? The net neutrality rules the president has just supported, which say that all bits must be treated alike, would mean that voice no longer goes to the front of the cellular service line. "You can't hear me now" would be the new commercial for all wireless providers if all cellular bits must be treated alike.

In short, it is a misreading of Internet history to claim that the Internet -- originally developed as a research network -- was designed to be a "dumb pipe," treating all bits the same. As the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation has argued, "contrary to such claims, an extraordinarily high degree of intelligence is embedded in the network core." What the net neutrality debate is really about is not whether the Internet will become like electricity or cable TV, but about whether it will progress and innovate over the next half century or be exactly like it is today: a network that does some things well (like deliver email) but many things poorly (like handle video calls).

Apply now for the 2015 information Elite 100, which recognizes the most innovative users of technology to advance a company's business goals. Winners will be recognized at the information Conference, April 27-28, 2015, at the Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas. Application period ends Jan. 16, 2015.

About the Author

You May Also Like