Will Your Company Be Fined in the New Data Privacy Landscape?Will Your Company Be Fined in the New Data Privacy Landscape?

The return of Data Privacy Week sees momentum continue for scrutiny on how data is collected, used, and controlled as regulators and the public sharpen their focus.

With robust regulatory enforcement of data privacy policies underway, with Meta and Sephora among those facing fines, other organizations may be working to comply with emerging data privacy laws at the international, national, and state level.

The trouble is, nuances of differences among regulations could lead to a hodgepodge of fines and other punitive actions for practices that might be acceptable in other jurisdictions.

A collection of stakeholders and experts in data privacy shared some of their perspectives for Data Privacy Week 2023 regarding compliance with evolving regulations and governance within organizations.

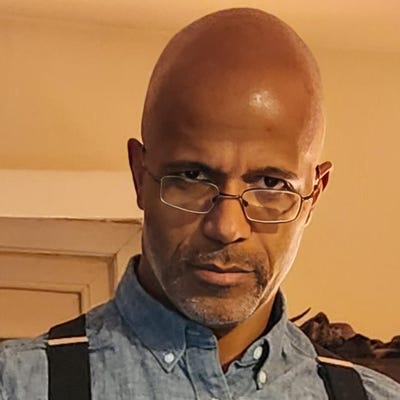

How data privacy regulations impact companies that leverage data in order to make money can be boiled down to consent, says Mark Ailsworth, vice president of partnerships with Opaque Systems. “Consent really is a legal construct as is expressed in GDPR [the EU General Data Protection Regulation] and a lot of privacy policies in a lot of companies that do business in the EU and certainly companies that advertise to EU audiences,” he says. In terms of data privacy, Ailsworth says consent goes beyond approving all cookies when visiting websites.

There can be layers to consent, he says, such as allowing digital behavior on the site to be tracked and linked to other digital actions for a set interval of time. “What consumers don’t really understand is the persistence of their consent on checking that box lives on,” Ailsworth says.

That initial consent can last for 90 days or longer, he says. “There’s a full-on marketplace that has really blossomed around the fact that consumers are clueless when it comes to understanding what consent is all about.”

The introduction and enforcement of GDPR have brought to light that many companies, Ailsworth says, have no idea how they should consent, and what their rights and privileges are to hold and transfer data.

US Political Climate & Data Privacy

The current political climate in the United States, he says, may play a significant role in whether national data privacy policy might be passed in the next 12 months. “While we have a Congress that is broadly interpreted to be rather dysfunctional this year -- from a legislative perspective let’s just agree on the fact there’s not a whole lot that’s going to come out of Congress -- I doubt we’ll see legislation, particularly binding legislation from a federal level.”

Ailsworth says more states have launched new data privacy guidelines for 2023 centered on providing consumers greater control of their data. “It is a weird, double-edged scenario,” he says. “Consumers want personalization, they want a relevant experience, and they want an experience that is tailored to what exactly they’re looking for.” What consumers might not realize is their data may be sold to third parties despite requesting such actions not be taken.

A mishmash of state regulations on the way could make it difficult, Ailsworth says, for chief privacy officers within companies to ensure they comply with such policies.

The varied policies being enacted across international and national jurisdictions are calling on companies to work in more thoughtful ways, says Ben Waber, CEO of Humanyze, with respect to data collection, analysis, and usage. “Just because something is legal in one jurisdiction doesn’t mean you have to do it or you should do it,” he says. “It helps to have a unified approach.”

Three types of data Waber says companies typically collect are internal data about employees and operations, data on products and services, and data about customers. Each type of data requires different thinking in terms of how that data is governed and used, with different disclosures and opt-in processes, he says. Having a data ethics committee, Waber says, including external members as advisors, is something companies should consider. “Moving forward, being intentional about data collection and analysis is something everyone should be thinking about.”

The old practice of collecting lots of data without clear intentions on its use seems to be coming to an end, Waber says. He sees a new era where companies must be very clear about their strategic objectives, what they need data for, and doing that in ways that minimizes harms that can come from data usage and manipulation. There will be tradeoffs though. “In France, you’re not allowed to collect demographic data,” Waber says. “That arguably creates more harms than it protects.”

For example, if a service was discriminatory against minorities, demographic data would still be necessary to examine the issue. “If you don’t have that data, it doesn’t mean discrimination doesn’t happen it just means you don’t know about it,” Waber says.

Privacy Legislation Like GDPR

While there has been increased chatter about US federal privacy regulation eventually coming, a growing list of states are implementing privacy legislation modeled after GDPR, says Dana Simberkoff, chief risk, privacy, and information security officer with AvePoint. The enforcement of such policies is being felt.

“Some large US companies are continuing to be dealt pretty significant fines,” she says. “The regulation and fining of companies like Meta and others have raised consumer awareness of privacy rights. I think we’re approaching a perfect storm in the US where the rest of the world is moving toward a more consumer-protective landscape, so the US is following in suit.” This includes activity by state policymakers as well as responses to cybersecurity breaches, Simberkoff says.

She sees the conversation on data privacy being driven by increasingly complex regulatory requirements and consumer awareness of data privacy, which can include identity theft or stolen credit card information. “I think, frankly, companies like Apple help that dialogue forward because they’ve made privacy one of their key issues in advertising,” says Simberkoff.

The elevation of data privacy policies and consumer awareness might, at first blush, seem detrimental to data-driven businesses, but it could just require new operational approaches. “I think what we’re going to end up seeing is a different way of thinking about these things,” she says. “There’s historically been a perception that it is ‘us’ and ‘them.’ That we have our identity as individuals and then we have our corporate workspace and then we have our public personas. But I think identity now is the new perimeter.”

With more individuals working from home, intertwining home life with work life and public life, who they are and what they do is becoming more integrated into the rest of society, Simberkoff says. “If companies are tracking you when you’re shopping online and then you log into your kids’ school program to check their grades and then you go over to work and those ‘who you are’ pieces aren’t segregated properly -- there’s this blending that becomes really scary for people.”

With more countries and regions enacting laws, and after working on data protection law for more than a decade, the current clime is the hardest it has been, says Lesley O’Neill, chief compliance officer with Prove. “We’re running up against privacy laws that are in every region.” This can include additional layers of scrutiny by country, which can be rather restrictive in France or Germany, she says, while the United States continues to deliberate its approach.

“Right now, the national, comprehensive federal law that’s out there is very protective compared to the current state laws that are out there, but we’re not even sure it’s even going to pass,” O’Neill says. “So, you’re trying to prepare for something that may or may not be.” Prove has looked to GDPR as a kind of gold standard on privacy policy, she says. “If you comply with GDPR, you’re pretty set around the world, but you have product people and innovation to take into consideration.”

Low-Risk Compliance

Companies have to figure out low-risk compliance for their operations, O’Neill says, even for an identity solutions provider such as Prove. “We’re trying to combat fraud,” she says. “We’re not doing anything that those specific laws are really designed to protect consumers from. I feel we’re in a really tough position because all of those laws are out there protect consumers when we’re out here to protect consumers from having money laundered or stolen.”

Though many business sectors are scrambling now to adapt to data privacy policies, healthcare has some history with increasing regulatory demands such as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), in regard to patient privacy -- and yet there continue to be challenges. “This has been going on for a long period of time, but it seems like for whatever reason, we as an industry don’t have our arms around it,” says Elizabeth A. Delahoussaye, chief data privacy officer with Ciox Health, speaking on patient right of access and other enforcements by the Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

“OCR is still issuing fines around patients filing complaints that they’re not getting their information in a timely fashion, that they’re not getting the information in the format they’re requesting,” she says. “We’re seeing tons of that.” For instance, regulators might inform medical practitioners that patients have filed complaints to obtain records, but if the practitioner does not respond, it can lead to the filing of a second complaint, Delahoussaye says. A lack of response can lead to the opening of formal investigations into medical practitioners that can carry civil monetary penalties.

Despite the shifting political landscape making it uncertain what new policies might be enacted, the matter of data privacy regulation is not going away. Regulators in healthcare, for instance, are cracking down, she says, which should not come as a surprise. Back in 2018, the director of the OCR laid out a warning at the HIPAA Summit conference, Delahoussaye says, about his office’s intent to issue civil monetary fines. The first penalty, issued in 2019, caught the healthcare industry’s attention -- at least for a moment. “I think a lot of people assumed that when there was a change in the administration that this would slow down,” she says, with a different party overseeing the federal government. Even with that change, the core players at the OCR remained who had been given the directive to ensure patients had that right of access, Delahoussaye says.

What to Read Next:

Special Report: Privacy in the Data-Driven Enterprise

Read more about:

RegulationAbout the Author

You May Also Like