Healthcare IT In The Obamacare EraHealthcare IT In The Obamacare Era

Modern technology created the opportunity to restructure the healthcare industry around accountable care organizations, but IT priorities are also being driven by the shift.

Read the new issue of information Healthcare

Read the new issue of information Healthcare

(registration required).

Despite all the attention focused on health insurance reform by the problematic launch of HealthCare.gov, the biggest impacts on healthcare organizations are likely to come from other measures embedded in the 906 pages of the Affordable Care Act legislation that squeaked through Congress in 2010.

Obamacare endorsed a structural change in the way hospitals and healthcare organizations get paid, based on how well they keep a given population of patients healthy rather than the number of patient visits or procedures they perform. This twist on the concept of managed care, known as an accountable care organization (ACO), is a strategy for improving the cost-to-value structure of Medicare. And it's expected to have technology and other ripple effects throughout the healthcare and insurance industries.

How quickly and completely this transformation will occur is debatable. Most of the people we interviewed see it as inevitable but likely to take a decade. Yet because this transition will rewrite the rules of care delivery and billing, organizations will have to make countless information systems changes to compete effectively as ACOs. For example, Sharp HealthCare in San Diego, which participates in both government and commercial ACOs, is working through at least half a dozen major system changes in order to support ACOs effectively, says CIO Bill Spooner.

Care management is "like CRM for healthcare."

Care management is "like CRM for healthcare."

-- Bill Spooner, CIO, Sharp HealthCare

In some ways, ACOs are reminiscent of the health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that arose in the 1970s. "They failed in large part because there wasn't any data," says Cynthia Burghard, an analyst who covers healthcare IT at IDC. Early managed care efforts talked about encouraging preventive care, but they focused mostly on containing costs. They introduced "capitated" models, limiting how much a provider could get paid for a given type of care, without providing tools to help providers become more efficient, Burghard says.

Today, the lack of data isn't a problem, though making effective use of it can be.

A few provider organizations such as Partners HealthCare have already shown that it's possible to find an ACO win-win by generating millions of dollars in Medicare "shared savings" to be split with the federal government. Yet others are frustrated by the lack of results they've been able to achieve through that same program, and nine of the 33 institutions that Medicare picked as its Pioneer ACOs dropped out of the program last year.

This is the "Obamacare era" of regulatory change, though some elements are really a continuation of policies initiated under the Bush administration. President George W. Bush started what became the federal government's Meaningful Use program, promoting the use of electronic health records and other health systems. Funding for Meaningful Use arrived in the HITECH Act, which was part of President Obama's 2009 economic stimulus program.

While Meaningful Use and the Medicare ACO program are the result of separate legislation, ACOs aim to take advantage of a modernized health IT infrastructure and exploding volumes of data being gathered, while at the same time putting pressure on IT pros to improve those technologies and analytics.

The broader trend is called population health management -- the idea that by focusing on improving the health of entire populations of individuals, healthcare organizations can deliver better care, more cost effectively. One way to drive that change is to move away from the traditional fee-for-service model, whereby healthcare providers can earn more from sicker patients who require more office visits, hospital admissions, and surgical procedures.

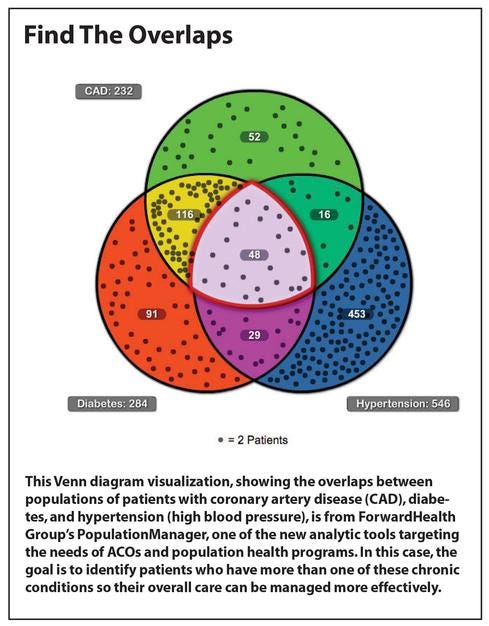

Figure 2:

Reformers refer to these as "perverse incentives" that drive overutilization, resulting in episodic "sick care" rather than a systematic effort to improve people's health. If what we want instead is a healthcare system that makes people healthier at a reasonable price, the incentives should reward preventive care that reduces the need for those visits, admissions, and surgeries.

The ACO concept has been kicking around since at least 2006, when it was introduced as a Medicare reform proposal. The first ACOs actually came from

private insurers, while lawmakers and regulators mulled over the idea. Now, because the government's Medicare program is the largest insurer of all, its endorsement of the ACO model reinforces the idea that this is the wave of the future.

"If Obamacare does anything, it encourages people to get coordinated more quickly," says David Muntz, a former deputy director of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, which oversees the Meaningful Use program. Muntz now serves as senior VP and CIO at GetWellNetwork, an online service focused on boosting patient engagement. Organizations may be changing because they see the benefits of accountable care or because they're "trying to survive in spite of it," but they will all have to change, he says.

"The ACO model was a logical outgrowth of the challenges we were seeing on the financial side of the business," Muntz says.

Surviving accountable care

Whether intended or not by lawmakers, the new regulatory regime may also drive further industry consolidation, since sole practitioners and small practices will find it even harder to compete with large organizations that can assert more comprehensive control over patient care. If providers are asked to take responsibility for all aspects of a patient's care, they'll want to have control over as much of it as possible.

That consolidation is already happening, Muntz says. "Providers who are weary of the changes or don't want to take the time to understand all the changes are lining up with hospitals," he says. Remember, he adds, "we're still supposed to be focused on the patients. It's not all about the money -- it's how do you get the patients engaged in their own care?" If the structural changes in the market achieve a better quality of care, he thinks the transition will have been worthwhile.

"You can't buy, quote, a 'population health management tool,'

"You can't buy, quote, a 'population health management tool,'

because it isn't one tool. It isn't a module."

-- James Noga, CIO, Partners HealthCare

When hospital CIOs talk with Muntz about the pressures they're facing, they talk less about Obamacare than about their organizations assuming more risk in general, dealing with both public and private payers. That means they need to do a better job of coordinating care across all the doctors and nurses in their networks, as well as with the patients themselves, he says.

As a former hospital CIO, Muntz says he regrets the collective effect of piling so many requirements onto technology managers at once. "If all they had to do was Meaningful Use, it would be fairly straightforward," he says, but the steeper requirements of Meaningful Use Stage 2 are hitting at the same time as many other requirements, such as the shift to ICD-10 coding and the need to adapt to accountable care. Big hospitals may be up to it, but smaller and rural providers are struggling. "On the other hand, if we hadn't put a stake in the ground, would they have moved at all?" he says.

The ACO pioneers

Partners HealthCare is one of the big organizations that seems to be up to the challenge.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services picked Partners as one of its Pioneer ACOs, organizations charged with proving the value of the model and attempting to create "shared savings" -- saving money for the government and itself. In mid-2013, Partners announced that in its first year in the program, it had generated about $14.4 million in savings to be split with the Medicare program. Partners has also been cutting similar deals with commercial payers.

"When we talk about population health management, we think about it holistically, not necessarily just in terms of the Medicare population," Partners CIO James Noga says. "We anticipate more and more payer contracts in which hospitals and healthcare systems will continue to take on additional risk."

That trend started before the passage of Obamacare, but "the ACA probably put it more in focus," Noga says. Despite the demands this regulatory push places on his organization, Noga says it's a push in the right direction. Being less reactive and doing a better job of following up on patients with chronic conditions is the industry's best chance of "bending the cost curve" while improving the quality of care, he says.

Partners is betting that as private insurers see Medicare lowering costs with this approach, their interest in ACOs will intensify, Noga says. "For us, it's a strategy," he says.

The trend toward ACOs and population health management has driven Partners to retool. It's the impetus for a major Partners initiative to consolidate patient data onto one EHR, Epic, from the several it has at different hospitals. On the other hand, because Partners is only getting started on what will be a

five-year rollout of the Epic software, it will still have to deal with a blended environment for some time to come. For example, Partners will continue to refine a patient portal developed internally, even though at least some elements of that portal will eventually be supplanted by Epic's MyChart.

Nor is an EHR necessarily the be-all-and-end-all platform for population health management, Noga says. Caregivers will need analytics dashboards that help them identify individuals and group them into populations with common chronic conditions, such as diabetes, so they can devise strategies for better managing their health. Clinical decision support tools need to guide medical professionals toward delivering the best evidence-driven care. Primary care physicians need to get automated alerts when a patient in their care is admitted to the hospital or visits the emergency room, as well as follow-up reminders. Continuous monitoring of patients via devices in the home will become increasingly important.

"You can't buy, quote, a 'population health management tool,' because it isn't one tool. It isn't a module," Noga says. "You need many things to be able manage populations."

Sharp HealthCare CIO Spooner says he comes to the ACO model with experience in other forms of managed care, since California has long been a hotbed of activity with capitated payments for patient care. However, he discovered that ACOs, as implemented by Medicare, are significantly different. In particular, the government assigns each ACO a pool of patients whose health it is supposed to manage, but it doesn't limit Medicare recipients to getting care from providers in the ACO network, presumably for fear of limiting patient choice.

"There are more patients who are voters than there are providers, so we're outnumbered," Spooner says.

In a Medicare ACO, networks of providers are assigned patients to whom they have historically provided care, but it's up to the ACO to keep those patients coming back and to get them to proactively manage their own health. Online patient engagement is one of the most critical technologies here. It's a means of creating "stickiness" so that patients continue to work with a hospital for the same reason Amazon.com customers keep buying from that website. "You need to be the most attractive, engaging proposition in town," Spooner says.

"Our organization has been able to set up as an integrated delivery network, and that's just a blessing right now."

"Our organization has been able to set up as an integrated delivery network, and that's just a blessing right now."

-- David Lundal, VP and regional CIO, Dean Health System

Sharp created its own patient portal three to four years ago, allowing it to start building an online relationship with patients, although Spooner acknowledges "we're a long way from Amazon.com." Recognizing that commercial patient portal products have advanced significantly in the past few years, Spooner says Sharp will probably convert to one of them soon.

Care management or case management is another essential technology Sharp is struggling to address more effectively, Spooner says. "It's like CRM for healthcare -- you want to be tracking the patient in everything they're doing and be handing off the information more than just transferring medical records," he says. In complex cases such as cancer treatment, it's essential that strategies for follow-up care accompany the patient record, he says.

IDC's Burghard says the biggest IT challenge is probably analytics. Most providers have been relying on their EHR platform vendor, rarely the best call, she says. "Those are all transactional systems, and their strength is not in the analytics," she says, creating an opportunity for vendors of niche population health analytics applications.

In many cases, ACOs are formed by networks of hospitals and providers that use several EHR systems. "Bringing all that data together in a meaningful way is a challenge both from a technological perspective and almost more so from a domain expertise point of view," Burghard says. The software alone can't do the analysis, and there aren't enough talented informaticists and biostatisticians to go around, she says.

The expectations for ACOs are also likely to be ratcheted up, Burghard says. "A lot of successes of the federal programs as well as the commercial programs is pretty low-hanging fruit -- like keeping people out of the emergency room and reducing readmissions," she says. "Clinical improvement is the really tough nut to crack." In other words, the more worthwhile goal is detecting the best patterns of care, feeding them back to clinicians, and then achieving improvements in the practice of medicine.

Not everyone is eager to get started.

Robert Budman, chief medical information officer at Yuma Regional Medical Center, says an ACO could make a lot of sense in Yuma's southwestern Arizona area, given that there's "no other hospital for 50 or 60 miles in any direction" and that the community has a large Medicare population. However,

he balks at the challenge of assembling all the physicians in the area into an organization with the capacity to provide comprehensive care for 5,000 or more Medicare patients (CMS's minimum threshold for participation).

"We have 100 projects to do, maybe more, and only money to do a handful, so we have to choose very wisely which ones we're going to do -- and ACO is a huge one," Budman says. "It's a gargantuan undertaking, and it's got to be done right."

In other words, implementing an ACO is something his organization will want to do eventually, but it doesn't need to be among the pioneers.

New and existing networks

For other organizations, the ACO model isn't that big of a change. Integrated healthcare delivery networks such as Kaiser Permanente that both provide care and finance that care have arguably been operating as ACOs all along. Other health systems that offer their own insurance plans also have experience with the financial risk of the healthcare business.

"Our organization has been set up as an integrated delivery network, and that's just a blessing right now," says David Lundal, VP and regional CIO at Dean Health System in Madison, Wis. "We're at risk for about 40% of our business, so if we manage care well, it's in our best interest to do that."

"Care coordination will ultimately become better."

"Care coordination will ultimately become better."

-- Shafiq Rab, CIO, Hackensack University Medical Center

That doesn't mean Lundal has all the answers. Probably the most essential enabling technology is the electronic medical records system, Lundal says, and he feels confident in his organization's implementation of Epic. "We've got the EMR behind us, and that's the biggest thing we'll ever do," he says. "On the other hand, there was something relatively straightforward about implementing an EMR. It pushes you to do the biggest and hardest thing you've ever done over the course of five, six, seven years. This new stuff, there is not a road map -- it's more creative and inventive."

For example, addressing the goal of helping diabetics manage their disease better requires a strategy for analyzing data from the EMR, but also integrating other data sources, such as laboratory records. Population health management means analyzing the conditions that drive patients to the emergency room and strategizing to divert them to lower-cost care at their doctor's office, or via a video telemedicine consultation.

Lundal says one of his challenges is preventing the IT staff from becoming too bogged down in meeting regulatory requirements so they will have time for more innovative work -- a sentiment reinforced last year at a meeting of information Healthcare's CIO advisory board.

When healthcare providers that aren't part of the same integrated delivery network come together to form an ACO, one of their key challenges is to make IT systems that were chosen independently all work together. "I'm begging people not to have 75 different EMRs," says Shafiq Rab, CIO at Hackensack University Medical Center, which operates a regional ACO in New Jersey that recently reported achieving $10 million in shared savings for Medicare.

While it would be helpful to have one EMR standard, for now Rab is trying to steer participants toward four or five preferred vendors. "And if the EMR does not totally integrate, then it's time to choose another EMR," he adds. Another base requirement is that participating providers must connect to a health information exchange. "If they're not connected with an HIE, it's not going to work out," Rab says.

In addition, Hackensack University Medical Center hired a company called Team of Care Solutions, which provides active care coordination management, data integration, and business performance management predictive analytics to help the ACO function better. New technology is required because "care coordination is never something people have ever been paid for," says Alan Gilbert, co-founder and chief growth officer for Team of Care. It used to be that follow-up communications with patients was something doctors were supposed to do in their spare time, whereas an ACO should be able to recognize that time as just as valuable as time spent on office visits, Gilbert says.

A few years from now, ACOs may be called by another name, but the basic idea of changing how healthcare services are valued and paid for will remain, Rab predicts. Once Medicare demonstrates that it can achieve real savings with this model, private payers will follow. "Care coordination will ultimately become better," he says. "As reimbursements are more guided by preventative care, this will have its own legs."

Read the new issue of

information Healthcare.

About the Author

You May Also Like